Poorly-designed charts in your slide deck can smother your presentation with confusion and invite mocking from your audience. Do you know the difference? In this article, we introduce four core principles for designing charts for slides, and then derive twenty practical guidelines you can use. We also feature many examples to illustrate these guidelines. Core Principles for Slide Chart DesignSlide Design Series

Before jumping into specific guidelines, let’s look at the big picture for a moment. Whenever you insert a chart into your slide deck, what are the core principles to keep in mind?

Each of these four core principles will be referenced below at the end of each guideline in square brackets, like this: “[Relevant]”. Guidelines for Designing Slide ChartsThese guidelines apply regardless of which slide software you are using, whether it be PowerPoint, Keynote, Google Slides, Prezi, or anything else. Guideline 1: Limit your slide to one point and (usually) one chart. [Relevant]One of the hardest lessons to learn about slide design is to simplify. Many of us add more and more content onto our slides because we mistakenly believe that more is always better. This faulty thinking leads us to create slides that are too complicated for our audience to read and too complicated for us to present. However, if we can break free from the “more is better” trap, we discover that simple slides work better. To achieve simplicity with slide charts, we usually need to limit slides to a single chart. (Yes, there are exceptions where two side-by-side charts are warranted, but these cases are very rare.) Then, be sure the chart has exactly one story to tell, and craft all aspects of the chart to tell that story. Guideline 2: Craft a slide title to make the meaning explicit. [Relevant]Want to learn more? Most slides with charts have topic-based titles, like “Sales Projections”, “Wins per Season”, or “Focus group Results”. Topics convey very little information to your audience. Instead, aim for assertion-based titles which state the significance of the chart explicitly. Since your audience members will read your slide title first, they will know exactly what to look for in your chart. For example, titles such as these make the meaning explicit:

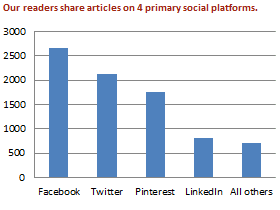

Guideline 3: Filter data to focus on the key relationship. [Relevant]A common mistake is to jam the entire data set into one chart without asking whether this is required or beneficial. This can cause clutter and readability problems which make it more difficult to understand the key message. Sometimes it makes sense to include the whole data set, but often this is overkill.

If you decide to filter data, you must choose whether to simply remove the extra values, or combine them into an “All others” data point. Either can work well; it depends on your situation. Slide Example: On the left, I have lazily introduced geographic data for 48 countries, resulting in a useless chart where most of the data relationships are obscured and the labels are unreadable. On the right, I recast the perspective by reducing down to five regional categories. This exposes visual insights in the data and results in labels that can be read.

Guideline 4: Highlight key data points with labels or color. [Relevant]When presenting with slides, your goal is to have the audience digest the meaning quickly, and then bring their attention back to you. Your presentation time is limited; you rarely have the luxury for your audience to study one chart for fifteen minutes as if it were a report, an academic article, or a book chapter. To augment your words, you can use annotations or contrasting colors to draw attention to the most important data points or trends. See the examples in Guideline 8 (annotations) and Guideline 11 (color) which support this idea. Guideline 5: Choose a chart type which aligns with your message. [Relevant]A junior colleague of mine once gave a data-heavy technical presentation, and every chart in his slide deck was a bar chart. When I asked why he used so many bar charts when other types of charts would have better fit the results he was trying to show, his reply was “I was aiming for consistency.” Yikes! Here’s the thing. Consistency is a trusty sidekick in a presentation, but never sacrifice clarity or comprehension to achieve it. Always choose the chart type which best aligns with your message by highlighting the key relationship or trend. For example:

There are so many chart options that it would take a separate article (or a whole series) to cover them all. The Financial Times Visual Vocabulary is an excellent resource which summarizes many options and highlights their strengths to convey certain types of messages. Guideline 6: Go big. Use the whole slide. [Readable]I cry a little whenever I see a chart occupying a tiny little region in the center of a slide, surrounded by miles of white space on all four sides. To aid overall readability, size the chart so that it uses the available space on the slide. (This one action will set you up for success with the next few guidelines too…) Slide Example: On the left, my slide software chooses a very small chart size by default when I use the “Insert Chart” function, resulting in a ton of wasted space. On the right, I filled the whole slide, resulting in a slide which is far more readable for the audience. Note that I have applied several other improvements in the “After” slide:

Guideline 7: Use large fonts. [Readable]Want to learn more? All of the chart text — axis labels, data values, annotations — should be readable by your audience. This text doesn’t need to be the same point size as your slide title, but it does need to be large enough to be read from the back of the room. When creating your slide deck, it’s easy to choose a size which is comfortable for you based on your computer screen. (e.g. 14 point text looks plenty large for me on my screens.) But this will usually lead to text that is far too small for the room where you will present. Depending on your room size and the screen size, 20, 24, or 28 point may be more appropriate. Guideline 8: Label the axes with sensible units. [Readable]This is really two guidelines in one. First, label your axes! Don’t assume that your audience will “just understand” what the axes are. In addition to labelling them, it’s generally good practice to describe the axes verbally when you introduce the slide. The last thing you want is for your audience to guess at what the axes are; if they guess wrong, they can walk away with a very distorted understanding of the chart. Second, be sure to choose sensible units. For example, if you are presenting a chart with your country’s national budget, don’t use dollars as units. Use millions or billions of dollars. This allows the accompanying data values to be short (e.g. “29.7” million dollars instead of “29700000” dollars). When your data points have lots of zeros, there’s a high risk that someone will read it wrong. (Quick: Is “34500000” equal to 3.45 million? Or 34.5 million? Or 345 million?) One final note… be careful with acronyms or abbreviations in chart labels. If you use an unfamiliar term, you will cause confusion for your audience. Slide Example: On the left, the vertical axis uses the default units (page views), which results in very large numbers being displayed (up to 100,000). On the right, I changed the vertical axis to display thousands of page views, so the axis labels are now easier to read (10, 20, … 100). Note that I’ve made several other improvements in the “After” slide:

Guideline 9: Avoid data label clutter. [Readable]If you have a “large” data set (e.g. 75 years of historical data), labelling every point may cause labels to overlap or look ridiculous. You don’t need to label every data point. It is usually sufficient to label the first, the last, and regular intervals in between (e.g. 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, 2010). Guideline 10: Avoid legends when possible. [Readable]For complicated charts (or diagrams), detailed legends are invaluable. However, you should rarely have a complicated chart in your presentation slide deck! (See Guideline 1 and Guideline 3.) For many charts that are simple enough to present in front of an audience, you don’t need a legend. The individual lines, bars, points or pie slices can be labelled directly. You will reap two benefits by removing it. First, your audience will not need to gaze back and forth repeatedly between the chart data and the legend. Second, by eliminating the legend, you can often resize the chart itself to be larger, which makes it more readable (i.e. Guideline 6) Guideline 11: Use a few high contrast colors. [Readable]If you use the default settings in many slide applications, you’ll end up with a smorgasbord of colors — possibly a different one for every data point. There is no value in this; it’s just visual noise! Instead, reduce the color palette to just a few high-contrast colors. Many in the data visualization community recommend using a muted color (e.g. grey) for “normal” data points, and using a high salience color (e.g. dark red or blue) for “highlights”. Slide Example: This normal-vs-highlight strategy is illustrated below. On the left, the slide software default gives one color per data point. On the right, I chose to use color to highlight the data point which emphasizes the slide’s assertion about book reviews.

Ensure that you have enough contrast to be distinguishable in either bright or dark room lighting. Finally, no matter how many colors you choose, be kind to people in your audience who may have visual conditions such as color-blindness. Guideline 12: (Re)Build the chart in your slide software. [Beautiful]When the chart you are presenting has previously been published (e.g. in a report, in a journal, on a website), the easy thing to do is just photocopy it or take a screenshot, and then paste that onto your slide. Unfortunately, this is a case where “easy” translates to “lazy”. The message you send your audience is “I spent 30 seconds preparing this chart for you”. It’s far better to create the chart directly in your slide software. This gives you the flexibility to follow all of the guidelines in this article (and others too). You can filter data, adjust scales, select colors, and optimize fonts to produce the best possible visual for your audience. Guideline 13: Reduce formatting of text. [Beautiful]“If we can break free from the “more is better” trap, we discover that simple slides work better.” Some presenters like to go wild with text formatting — like bold, italics, and underline — on axes labels, data labels, and other chart text. This isn’t necessary, and usually has a negative effect on readability and overall aesthetics. Instead, just reduce the amount of text (Guideline 8 and Guideline 9), choose a readable font size (Guideline 7), and leave the text unformatted. While the text needs to be readable, it doesn’t need to be the most salient. The chart lines, bars, or shapes should do the majority of the talking. Guideline 14: Remove backgrounds and borders. [Beautiful]Background textures and images rarely add any value at all; on the contrary, they cause readability problems. Borders are used to group and separate objects, and to help express relationships. But, if there’s only a single chart on your slide, there’s no need for borders. What are you separating the chart from? Ditch backgrounds and borders. Your slides will instantly look cleaner and more professional. Guideline 15: Avoid 3-D effects and other gimmicks. [Beautiful]Nothing prompts more slide mocking than useless 3-D effects on pie charts, bar charts, or other chart types. In addition to adding lots of visual clutter, 3-D effects actually distort relationships that rely on perceived area. (In)Famously, Apple CEO Steve Jobs once drew heavy criticism for committing this particular presentation error during a Macworld Expo keynote address. An equally bad design flaw is to introduce stacks of “objects” in place of horizontal or vertical bars. This is a visual gimmick that, at best, would have the audience laughing with you. At worst, the audience would be sneering at you. Usually, it’s sneering. The purpose of a slide chart isn’t to look “cool” or “high-tech” or “cute” or “modern”; the purpose is to clearly communicate the insights expressed by a data set. Ditch anything that gets in the way. Slide Example: In this example, there are two bad choices on display! (To see this chart done in a better way, see Guideline 11.) On the left, we have a 3-D bar effect which adds nothing and reduces the important visual relationship between the bar heights which encode the data. On the right, we replace normal bars with stacks of Six Minutes logos. (This may be the most awesomely terrible slide I’ve ever made!)

Guideline 16: Use consistent colors within your slide deck. [Beautiful]One of the most important reasons to build your chart within your presentation software (Guideline 12) is so that you can choose colors which make the chart look like it “belongs” in your slide deck. So, if your slide deck uses a blue-green color palette, then use the same blue or green tones as highlight colors on your chart. I know this seems like a trivial detail, but color consistency reinforces that your slide deck is cohesive. In turn, this will reinforce that your presentation conveys a cohesive message. If you have more than one slide with charts, make consistent color choices from slide to slide. For example, if you are presenting a series of charts comparing data from three sets (e.g. three countries, three regions, or three products), use the same color to represent each set on every slide. Once your audience has formed color connections on the first slide, they can easily digest subsequent slides. (Beware: If you mix the colors on subsequent slides, you will confuse your audience!) Guideline 17: Faithfully represent data. [Honest]There are many ways to distort, mislead, or lie with charts. Because a typical chart slide is only displayed briefly, audience members have to scan quickly and form opinions in a few seconds. Many people don’t have a strong background in mathematics or statistics, and they may trust a speaker unconditionally. The situation is ripe for spreading misinformation. Resist the temptation to do this, no matter what benefit you or your organization may derive from this misdirection. If you “get away with it”, you have crossed an ethical boundary; if you don’t, you will lose all credibility from your audience’s perspective. Both are disastrous results. “Consistency is a trusty sidekick in a presentation, but never sacrifice clarity or comprehension to achieve it. Always choose the chart type which best aligns with your message by highlighting the key relationship or trend.” Guideline 18: Verify data sources. [Honest]Before you present a data set with a chart, ask yourself the following questions:

The answer to all three questions must be “yes”. If you have any doubts, then it is better to be cautious. Cut it out and either find a more trustworthy data source, or figure out a different way to convey your message. Guideline 19: Credit your data sources. [Honest]Just as with all external sources of evidence (e.g. quotations; facts; theories), you should credit your data sources. Whether you declare this verbally or not, you should mention the data source on the slide itself. You can do this in small print at the bottom of the slide. Guideline 20: Offer complete data to your audience. [Honest]Many speakers tell me that the reason they create crowded charts (in violation of Guideline 1 and Guideline 3) is because they want to “show the whole data set” to their audience. While this is an admirable goal, it confuses the purpose of a presentation. A presentation is not a “data dump”. If you are effective, your audience will be educated, persuaded, or inspired to dig deeper into your message and your content, including the data. When you offer the complete data set(s) to your audience, you will be seen as honest and trustworthy. There are several ways to do this:

A guideline doesn’t work for my chart. Can I break it?I get asked this question every time I write an article which is guideline-based. The answer I always give is that beginners should always follow the guidelines until they become second nature. Slide Design Series

However, like all guidelines, there are cases when an exception is justified, and experienced presenters should be able to detect them. In those cases, jump back to the four principles at the top of this article. Ask yourself whether your guideline exception violates any of the core principles. If not, then you should be safe to use the exception. Your Assignment…Dig up one of your recent slide decks that included one or more slides with charts.

Please share...Share on Facebook | Tweet this | Share on LinkedIn | Save to delicious | |||||||||||||||||||||

Similar Articles You May Like... |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Andrew Dlugan is the editor and founder of Six Minutes. He teaches courses, leads seminars, coaches speakers, and strives to avoid Suicide by PowerPoint. He is an award-winning public speaker and speech evaluator. Andrew is a father and husband who resides in British Columbia, Canada. Twitter: @6minutes | |||||||||||||||||||||

| © Six Minutes, 2018. | |||||||||||||||||||||

Slide Charts: 20 Guidelines for Great Presentation Design

↧

↧

Well-designed charts in your slide deck can convey meaningful insights where words alone would struggle to do so.

Well-designed charts in your slide deck can convey meaningful insights where words alone would struggle to do so.